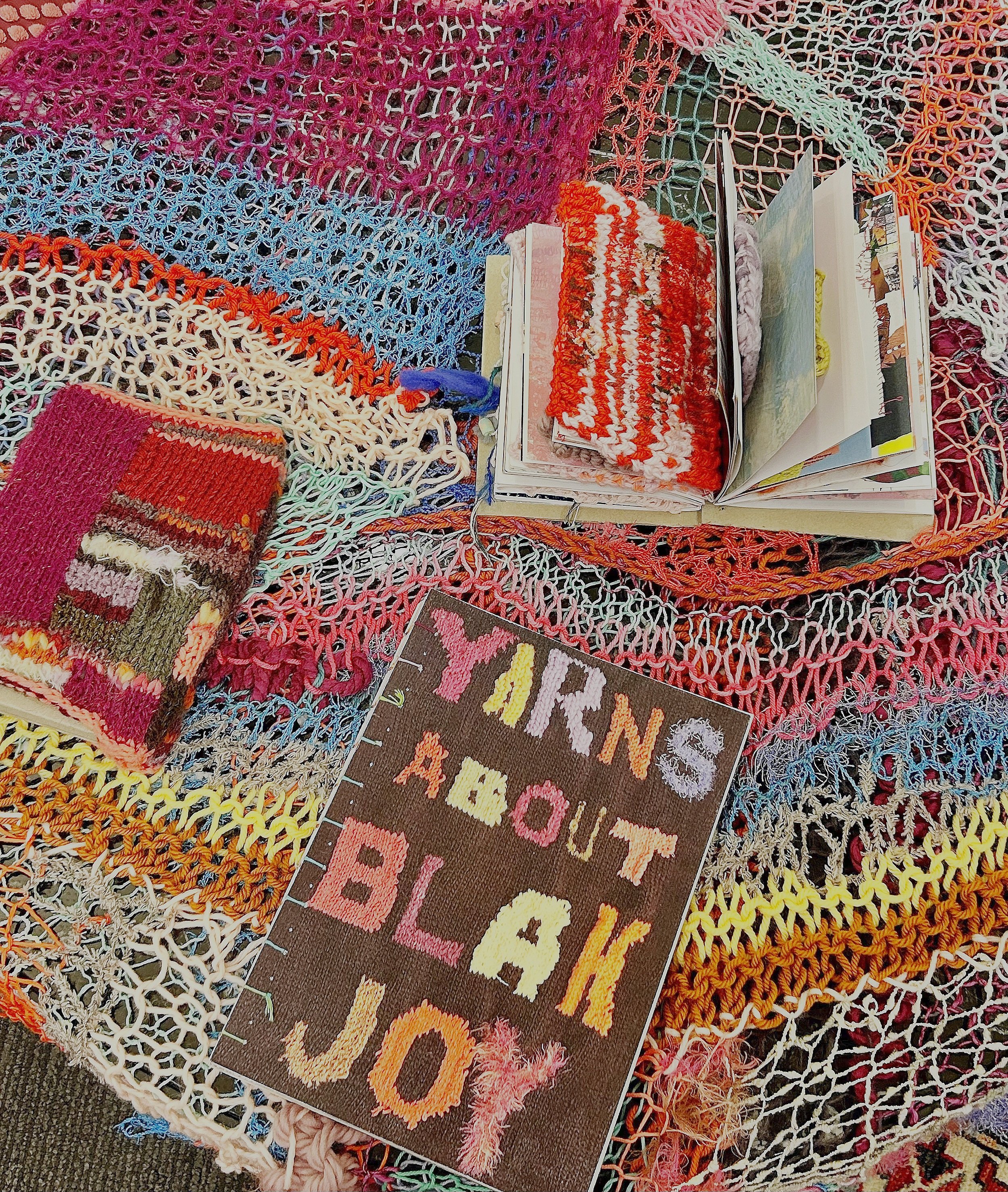

YARNS ABOUT

BLAK JOY

Sancia Ridgeway (she/her) | @scuzz_knits | Gadigal & Gumbaynggirr Country

Article by Joella Marcus (she/her)

Sancia Ridgeway is a Gumbaynggirr woman based on Gadigal land, Sydney. She is a graphic designer and fibre artist who specialises in knitting. She is a passionate, story-driven creative who uses her design skills and creativity to uplift and empower the voices of minoritised people through meaningful designs.

Her knitwear practice and commission works focus on colour and texture. Sancia hopes to do exhibition/art piece knitting to tell the often forgotten stories of First Nations and other minority groups. Central to her practice is sustainability and resourcefulness; many of Sancia's garments are 'scrap yarn' pieces - using yarn from leftover projects and op-shops. Sancia prides herself on how little waste she produces through her textile and artistic practice.

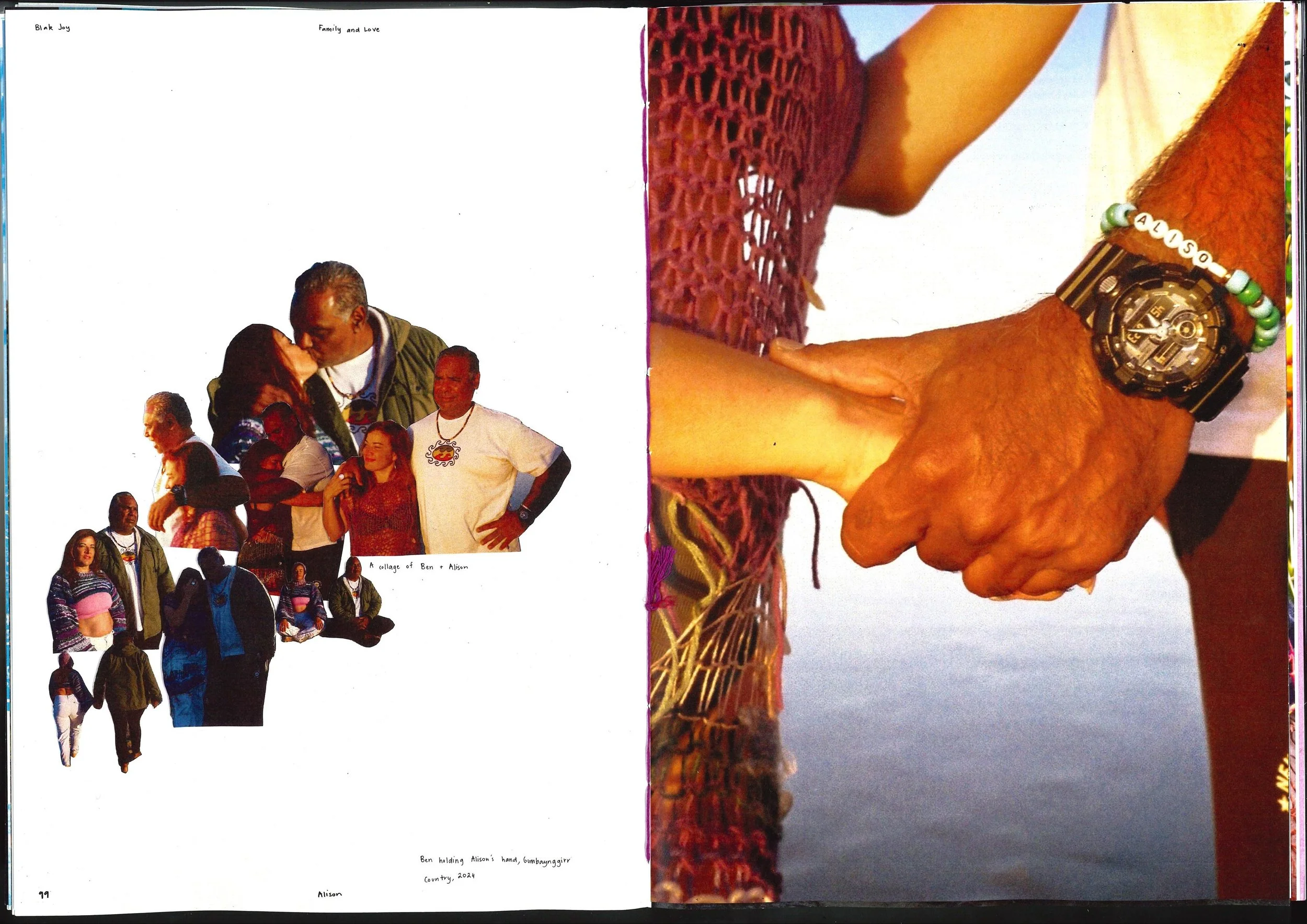

Sancia Rideway only began knitting in 2023 amidst days spent traversing European landscapes. Since then, she has committed herself to an artistic practice based on the fibre works of knitting and weaving – learning from YouTube and those who crossed her path. Sancia’s knitting practice has become a thread of connection to the people within her community and deepened her relationship with her family, in particular her late Grandma.

Sancia’s Grandma was a great knitter herself, and unfortunately passed before Sancia had the chance to learn from her, yet her newfound practice sparked a feeling of connection between them through the act of knitting alone. Her ongoing knitting practice inspired her recently completed Honours project Yarns about Blak Joy, which uses fibre-based works as a form of activism, self-determination and material representation of the Blak Joys within her community. With a graphic design background, she came upon knitting during a time of feeling disheartened with her degree, unsure about her future and torn between being an artist and designer. Upon beginning her Honours year, she resolved to immerse herself in an interdisciplinary practice and unshackle herself from introspective thoughts that forced her to place a capitalistic lens on her evolving and embodied artmaking.

Amongst a digitally saturated world, knitting is one of the few common manual practices or crafts in which you are still afforded the opportunity of mistakes, idiosyncrasies and a bit of individuality. As hobbies become commercialised and everyone struggles to re-learn the boundaries between pure creativity and profitable ideas, the beauty of mistakes are quick to be forgotten. Within textiles, especially weaving and knitting, mistakes can act as a marker of authenticity and skill. For example, Persian rug makers always leave one mistake as a sign of respect, as they believe they are not as divine, as perfect, as their God. This one mistake has so much power, and when you think about it in a binary logic, a mistake is given not one bit of grace. Instead, it's a disgrace.

As a freehand knitter, Sancia embraces the beauty of imperfection and allows for mistakes as she incorporates them as a natural outcome of her experimental approach. By deciding every step of the way where the piece goes, basically making it up, Sancia is able to relish in the playful essence of knitting unbound by patterns and using visual estimation against her own body to gauge the progress. Her appreciation for the mutable creative process is reflected in how mistakes are markers of success, a symbol of improvement, rather than faults in the outcome.

Due to Anglocentric economics and the artistic division of the Arts and Crafts movement, value is often allotted to practices that provide aesthetic pleasure over function. Art is heralded for its originality and creation, while crafts are perceived as merely an execution of convention. Knitting, as a craft, is commonly undervalued and underplayed. Its power lies in this disregard, as less emphasis is placed on perfection – only critical or trained eyes stumble over the very mistakes that make knitting a stress-free outlet. Disallowed in our workplaces, hobbies, and even in our personal lives, mistakes and stress-free outlets now few and far between. Sancia cherishes mistakes as a critical part of her creative praxis. She says “I'm not sure how we're supposed to grow and learn if we're not allowed to make mistakes”.

Inspired by her cultural and historical connections to Gumbaynggirr Country in the Coffs area, and as a Gumbaynggirr girl living on Gadigal and Gumbaynggirr Country, Sancia interlaces an ecological narrative into her patterns. This is exhibited not only in her dedication to using scrap yarns, eco-dyeing and donated fabrics, but in the shapes and elements she draws from her environment, such as fish netting, rusted corrugated iron, and her use of shells from Dharawal Country (with permission from Traditional Owners) and Gumbaynggirr Country. The eco-conscious theme is an intersection of emulating the lands on which she grew up on and the eco-anxiety prevalent in our generation, as we become hyper-aware of the ramifications of the Anthropocene. Sancia’s creative praxis and her deep explorations of equity and social justice seek to combat the struggle in reclaiming power when autonomy has been taken out of your hands. Harmonising ideas of memory, natural phenomena and identity, Sancia hopes to extend upon this by maintaining a net zero or waste free output. To achieve this she maintains a scrap yarn project, collecting all trimmings, even if they're only a centimetre long, colour-coding them and re-spinning them into new yarn. Additionally, she saves the yarn labels, which she hopes to recycle into new paper. Amongst the harrowing effects of government and corporations on the planet, these actions are one of the small ways she retains control and remains hopeful in her impact.

“It's really disheartening to watch … but if you're able to make this small contribution, it doesn't solve the big problems, but it does make you feel a little bit more hopeful … [and] that's what people need at the moment”.

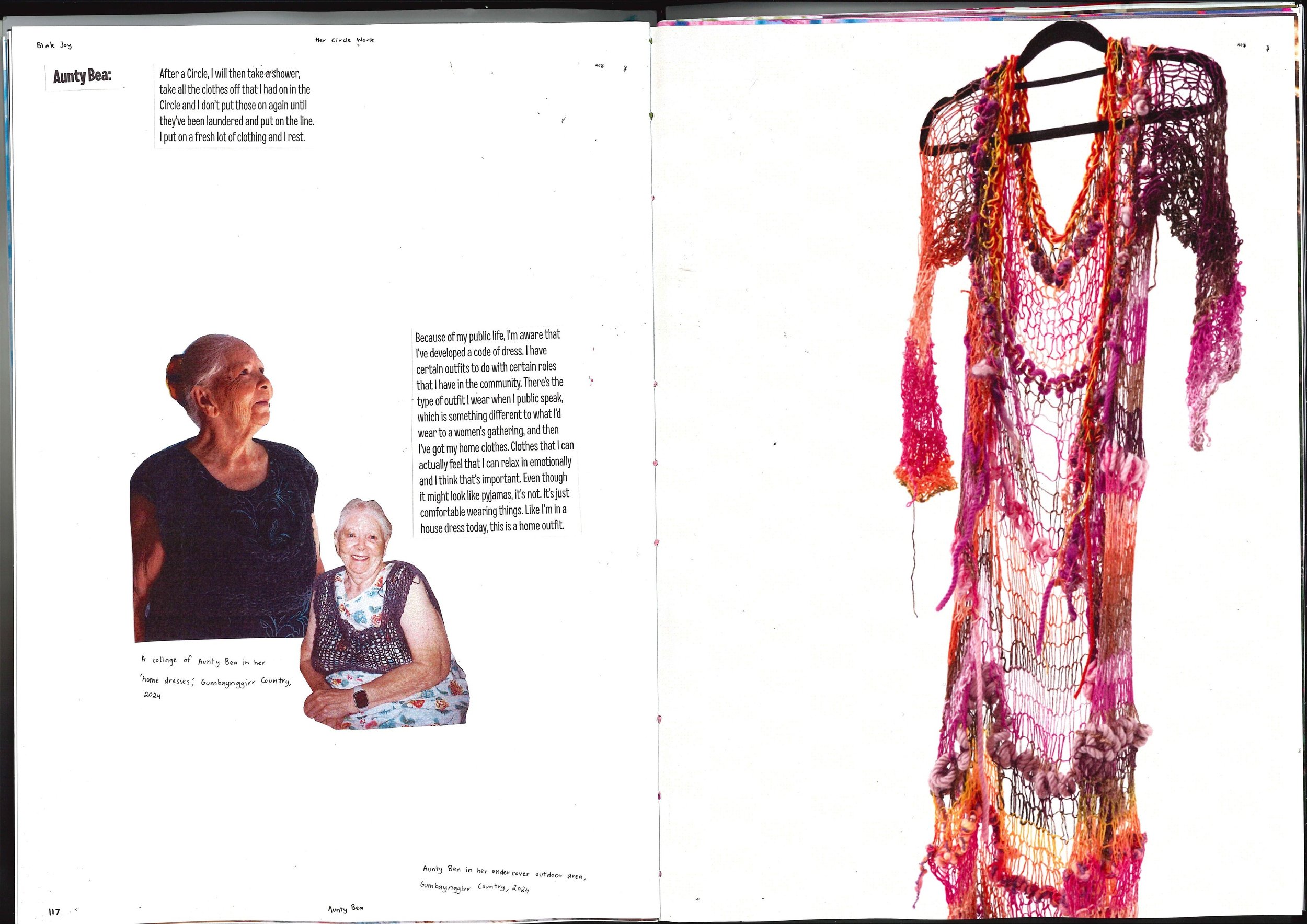

Sancia maintains authenticity at the forefront of her designs, not only in her approach but in who she designs for, and the real sense of being she manages to weave amongst the fabric of her pieces. Unable to be overwritten or corrected, freehand knitting allows for self expression and maintains a unique quality not only in its beauty but also in its function. Sancia enjoys taking an experimental approach that goes beyond traditional textiles, knitting pieces that best reflect and encapsulate the story of the person she is designing with. The fibres thus become a representation and collection of personal, cultural and political narratives.

For her Aunty Bea, Sancia knitted a cloak that represented her Aunty as an Elder figure; Aunty Bea quotes “I see myself as a person of repute and I own that”. Sancia admires her Aunty Bea as she is “set in her boundaries and she is self-determining every day”. Sancia felt pride in being able to give her something that many Elders in her community, amongst other things in life, weren't able to get – a rewarding exchange.

For Sancia’s Dad, she took a metaphorical approach to signify the mental analogies he uses to cope with the process of aging. Aging is often shunned, overlooked and discouraged in Western society, which when coupled with the fact that men are not encouraged to openly discuss their feelings, forces men to neglect their mental health. This patriarchal capitalist form of oppression particularly impacts First Nations men. Her Dad used metaphors about resilience such as “[being] Teflon coated”, “having a superhero cape”, or “put[ting] your Goanna skin on”, to process and reflect on the complexities from his own past and upbringing. Sancias’ personal totem is a Goanna; a spiritual emblem. It was given to her when she was ten years of age by her Uncle, an Elder in her community. Totems are a symbol that connect you to the lands, the spiritual world, and defines relationships and responsibilities within certain groups, including to the animal itself. The Goanna is a symbol for strength, adaptability and self-protection and links to Gumgali the Goanna from the Gumbaynggirr creation story. Now looking to protect himself, but in a way that's soft, the protective and shielding nature of the possum skin cloak was what he felt was fitting for his story. The need to take care of yourself in a society that isn’t set up with systems to do so was emphasised in the protective textiles Sancia crafted to help understand and portray her Dad.

The project Yarns about Blak Joy came to life six months after the ‘No’ outcome of the 2024 Voice to Parliament Referendum and was a response to emotional weight the result bore, including the ongoing inequalities First Nations people in Australia face. Unable to confront the negativity associated with the ‘No’ outcome and the repercussions that would ensue, Sancia decided to focus her efforts on a form of activism that would unite, not only those in her community, but other communities as well. A choice that would irreversibly change her outlook on how to discuss, enact and perform activism. Whilst acknowledging that there will always be a time and place to face the terrible daily occurrences enacted against First Nations people, Sancia's approach saw her redefine pathways to hope and liberation through rest, play and joy. Ultimately, choosing to acknowledge the sadness, the trauma and the negativity, but harnessing it as her own power by turning it into something positive, allowing her to dictate her own narrative.

The term ‘Blak Joy’ is an Australian reimagining of the phrase ‘Black Joy', originally coined by Kleaver Cruz in 2015 in response to the police brutality enacted against African-American people in the United States. Police brutality is an ongoing threat and assault for both those in the United States and Australia and is one of the many unfortunate similarities in the treatment of Black and First Nations People. Similar to pathways of liberation found in Freedom Rides and other US activist movements, Black Joys, whether in the US or Australia, allow individuals to hold space for both the joy and atrocities that happen in the world. Bla(c)k Joys are framed as any type of Joy, not tied solely to activism, that allows the individual reclamation of their peace and joy as a form of resistance.

Sancia’s Blak Joy is currently knitting, but her Joy is forever changing, “Your Bla(c)k joy doesn't have to be your one thing forever; it can move with you”. Taking notes from Tricia Herseys’ Rest Is Resistance: Free Yourself From Grind Culture and Reclaim Your Life, she draws inspiration from the interchangeable nature of rest and joy, as she noticed First Nations People have begun adopting rest as resistance. Bizzi Lavelle, a Wakka Wakka woman living on Quandamooka country, wrote an article for Refinery29 ““Rest Is Resistance”: Why 3 First Nations Women Have Chosen To Stay Home To Heal On Jan 26”” in response to feeling emotionally burdened and exhausted from the consistent inundation of realities they had to face; “Closing the gap, deaths in custody, police brutality, the referendum, Invasion Day, minority stress, systemic racism [and] regular day-to-day racism”. Seeking liberation in the power of rest, not as a disregard for the ongoing fight or lack of care, but as care for her own self worth and a disruption to capitalist mechanisms that enable white supremacy. Rest, as a form of activism that is unacknowledged as activism in the public forum, places the weight of responsibility off those who tirelessly face expectations of advocacy and engagement in public discourse.

As Sancia says “it's activism within yourself, choosing to boycott … taking time for yourself, particularly for minority communities … because there is a lot placed on your own shoulders to fight activism that you didn't necessarily ask for”.

Drawing parallels between the United States and Australia, the title of her Honours project, Yarns about Blak Joy, encapsulates the potential for shared understanding through mirrored circumstances without erasing individual cultural identities, acknowledging that each different group, every different pocket of society, still have their own unique individual features.

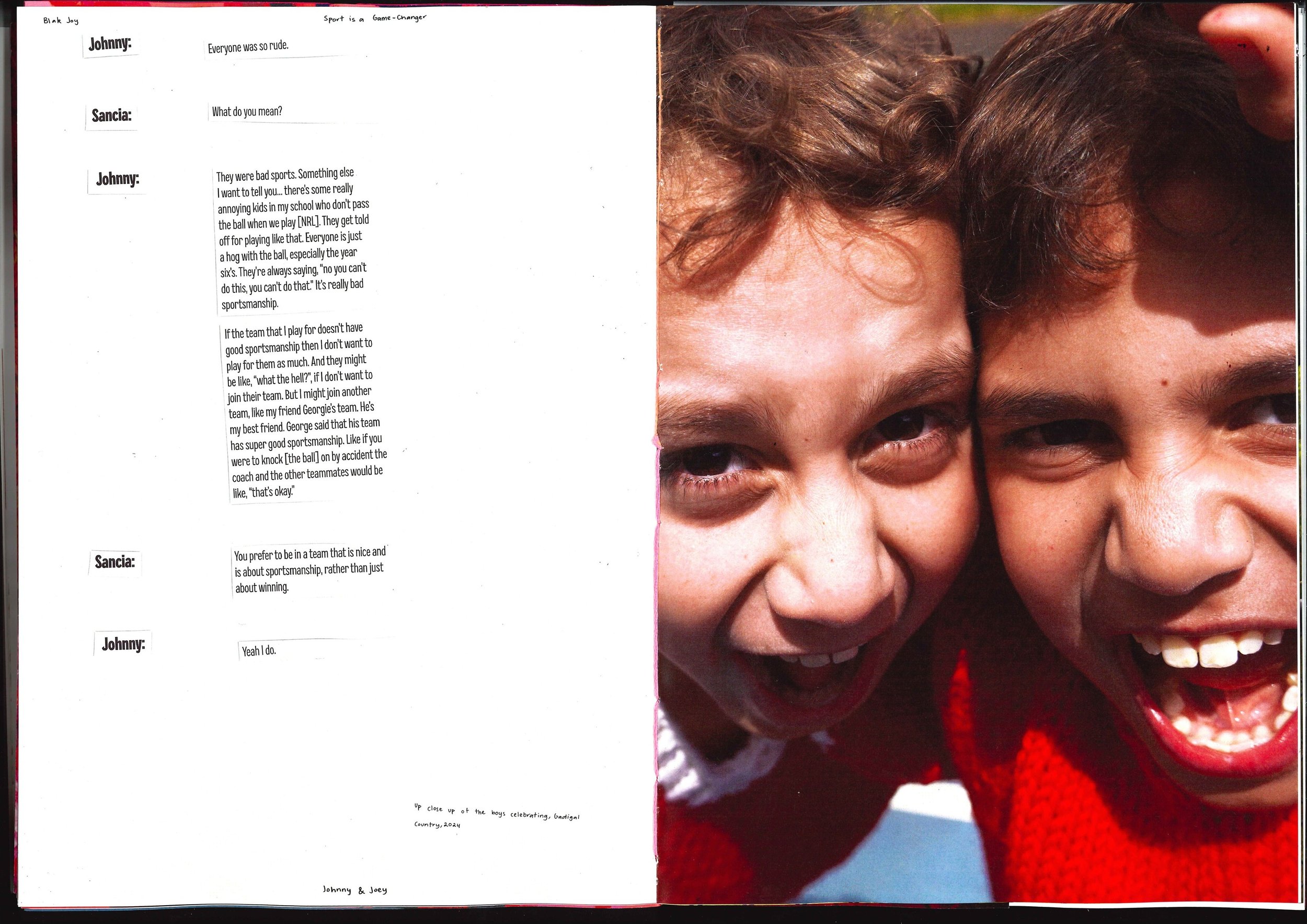

Focusing on knitting as her Blak Joy, Sancia explored the joys of those within her own community, looking to challenge perceptions and change stereotypes about First Nations people. The project began through conducting “interviews”, not so much with a Western methodological approach, but in inciting ongoing conversations that took place across days, activities and time spent together. These conversations laid the foundations for works of self determination and representation, as Sancia looked to present their story through the garments.

Translating such complex ideas into knitted works is a cumulative effort that builds upon the layers of history carried within fibre crafts. A functional art that began out of the necessity of the working class, hundreds of years ago in Scandinavian and/or Middle Eastern countries, it was originally a form of livelihood and an essential part of daily life. As part of her project, Sancia knitted a quote from Loretta Napoleoni’s book ‘The Power of Knitting; Stitching Together Our Lives in a Fractured World’ which discusses the intergenerational act of passing on the skill of knitting and how this connects a long line of women together throughout time. Fibre crafts have long been integral to society, however, are traditionally undervalued as a tool and an art form, due to their perception as a women’s craft. As a skill passed down from generation to generation through matrilineal lines, the transferral of expertise is very similar with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways of being and knowing, constructing a “big, interconnected woven stream of knowledge” Sancia explains. As a Gumbaynggirr woman, Sancia is part of a matriarchal tribe where women are the ones who are guiding the community. Sancia feels this special and sacred bond to her past mothers, grandmothers and elders and honours the intense feeling of belonging and connections that she has gained through embodying the work of her ancestors.

“I feel very connected through my matriarchal line, even though that's my dad's side of the family. I connect with his mothers, grandmothers and I always think about how in my life, the ways that I'm connected to them…every day.”

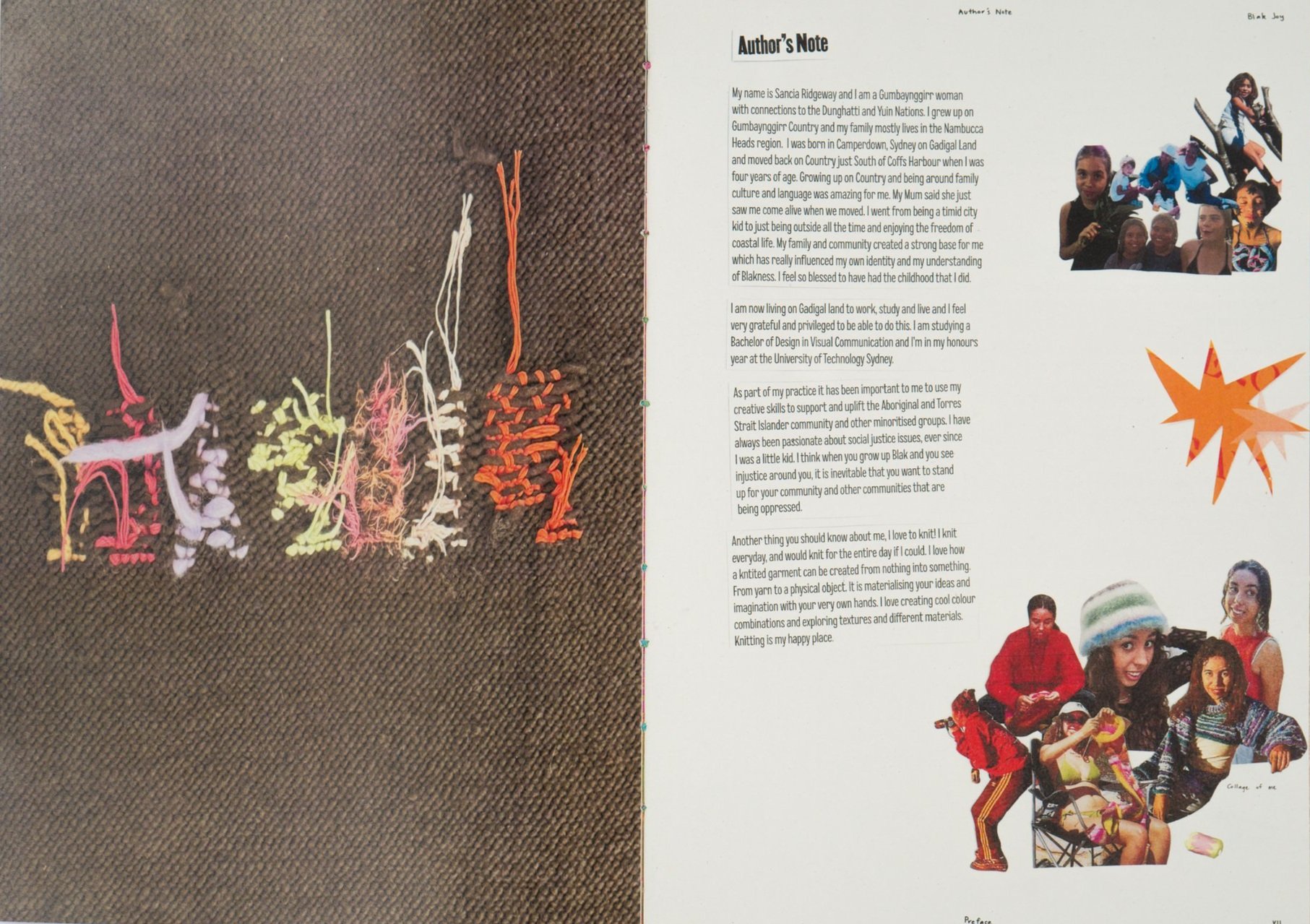

Now a unique fibre craft, knitting unlike many art forms provides function, form and aesthetics, encapsulating what design is; the intersection of practical things that we need and things that are beautiful. The final product Yarns about Blak Joy was a hand generated journal-esque scrapbook and 15 knitted pieces. The visual system and natural quality of the project positioned the important topics in an approachable manner, with Sancia hoping to absolve any accusation or alienation in her presentation. Crafting an understanding around the multi-faceted nature of identity, individuality and the disparate experiences of individuals, Sancia hopes to continue to tell “stories of people and of Country that need to be told”.Yarns about Blak Joy is the inception of Sancias’ ongoing practice which she hopes will continue to shape discourse outside of hegemonic narratives of resistance to the benefit of Indigenous Futurisms.

Credits:

Written and Interviewed by Joella Marcus (she/her)

Interviewee: Sancia Ridgeway (she/her)

Photography: Sancia Ridgeway